The "My Kid Could Paint This" Problem

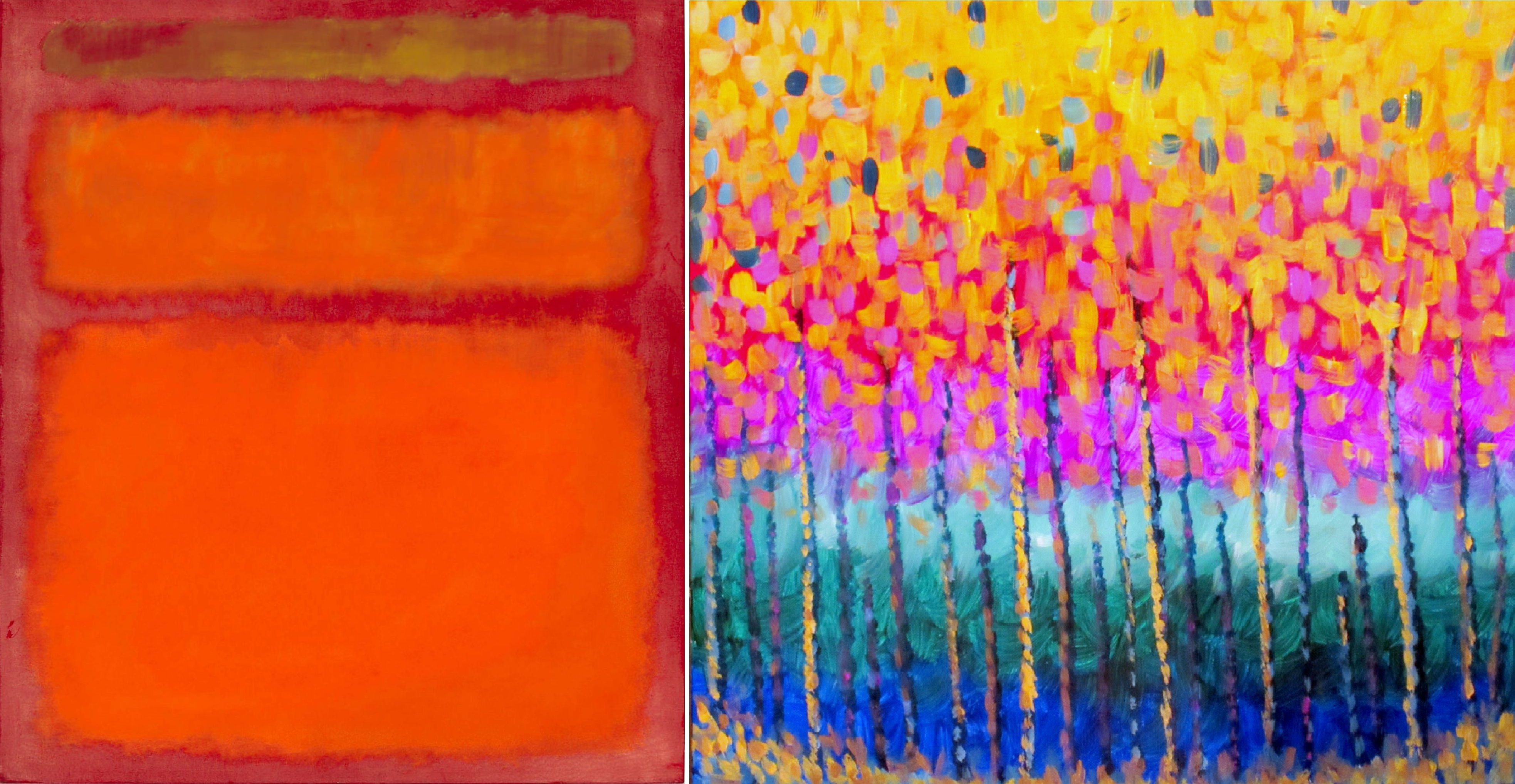

That being said, I’d like to pass on my own insights so that the next time you’re at a museum or gallery, you’ll be able to better appreciate the abstract art that you find there, and maybe even be able to explain to another visitor why their five year old would not actually be able to paint Mark Rothko’s “Orange, Red, Yellow.”

Keep in mind that there’s a difference between “painting” and actually producing “artwork”. The paintings in museums are ALL works of art. This means that they were made by individuals who painted, not only with some knowledge of technical applications, but also with a great deal of heartfelt intention. In other words: A painting is decorative, and a work of art (while still potentially decorative) is made to make the viewer feel something. An artist makes the painting with this difference in mind as they work. They create the painting so that people who look at it later can be moved, which they may do through purely aesthetic means, or by revealing something new to the viewer, or making a statement of some kind.

When an abstract artist works, this process is no different. They create their work of art with great intention. Even Dadaists- artists whom many of, prided themselves on producing artwork through random and uncontrolled means, were intentionally experimenting with the artistic process.

Abstract artist, perhaps more than any other kind of artist, must also have a firm grasp of the psychology of aesthetics, which we can define as a set principles derived from nature and associated with the appreciation of beauty. Basically “aesthetics” are “what makes art look good or bad.” Abstract artists have to manipulate colors and shapes that don’t usually look like actual objects, and fashion them in a way that will be appealing to a viewer on a psychological and subconscious level.

ALL artists with formal training study and experiment with aesthetics extensively. In fact, a firm grasp of aesthetics are not only something an art student must demonstrate in order to graduate, but are also what make a Pinot’s Palette painting popular. If you’ve ever checked out our calendar and found a painting that really struck you as stunning, it’s a clear indication that the artist who produced it is a master of controlling aesthetics.

Abstract artists are SO skilled at using aesthetic principles that they can use the tiniest details (such as nearly invisible variations of color, and brush-stroke weight) to enhance the aesthetic appeal of their paintings.

For example, Rothko’s aforementioned “Orange, Red, Yellow” painting is much more than it appears at first. Rothko’s expert understanding of aesthetics allowed him to create shapes that are perfectly portioned and balanced, and allowed him to know exactly where paint colors with subtle variations in hue and contrast. What appears simple at first is actually a complex work of art that can occupy a viewer’s interest, and appeal to their sense of beauty— Perhaps reminding them on a subconscious level of something they might also find in nature, such as a sunset.

To prove the importance of a honed knowledge of aesthetics, a study was conducted by Angelina Hawley-Dowen and Ellen Winner, in which children were asked to produce abstract paintings. These paintings were then paired side by side with abstract pieces that had been produced by well-known artists. Without recognizing any of the pieces, or knowing which piece was the professionally made, thirty-six participants (15 art students and 21 non-art students) were far more likely to prefer the professional paintings over the ones produced by children. They reasoned that the professional paintings seemed better planed, more interesting, and more visually pleasing.

Now that you know you have a little bit of artists insight yourself, I’d encourage you to visit your local museums and galleries to appreciate the abstract art there. Consider what statements the artist was trying to make, and why they chose to paint in the way that they did. And while you’re there, if you hear any other onlookers remark that their “kid could paint this,” just politely tell them “Yes, maybe they could, but they would need substantial practice, and a firm grasp of aesthetics.”

Have a fun abstract night out with us on Saturday, April 29th - "Abstract Forest"

- The Artist's Insight - A monthly blog special by Eric Maille -

I’ve been painting my entire life, but I think you’ll agree with me that being a painter doesn’t make you an artist. An artist must be willing to explore the fascinating world that exists behind paintings- a rich history of unique talents, creative imaginations, innovative techniques, and thoughtful self-expression.

I’ve spent a long time developing that insight and learning from the insight of others, and it's helped me to become a professional painter and illustrator living and working in Norman Oklahoma, and an instructor at Pinot’s Palette Bricktown. Now, once a month, I’ll be providing tips, tricks, and stories from a polished perspective, and an artist’s insight, so that even the casual painter, can become an art-lover and artist themselves!

Sincerely yours, Eric Maille

Share Sign Up for Abstract Forest TODAY! | Study by Angelina Hawley-Dowen and Ellen Winner